BUEC 311: Business Economics, Organization and Management

Topic 1: An Introduction to Managerial Economics

Andrew Leach, Associate Professor of Business Economics

aleach@ualberta.ca

leachandrew

@andrew_leach

Welcome!

- Some quick facts about me:

- I grew up in Ottawa

- I have degrees in environmental science, economics and law

- My academic interests are law and economics, environmental policy and energy markets

- I've also worked in various governmental advisory roles

- This is my second time teaching this class

Welcome!

- Beyond the classroom

- I have two kids aged 11 and 13

- I have a dog named Kona

- My main hobby is cycling, and I also play hockey and dabble in woodworking

- I have a serious Twitter addiction

- My expectations of you, your expectations of me

- Dealing with the circumstances

About This Course

Learning Goals

By the end of this course, you will:

apply economic models to managerial and government decisions

explore the effects of economic and political processes on market performance

- competition, market prices, profits and losses, property rights, entrepreneurship, market power, market failures, public policy, government failures

apply the economic way of thinking to real world issues

be able to access and interpret relevant economic data

Learning Objectives

- The language of economics

- What do you mean by...

- Economics as a tool for decision making

- How to use economics to become a better manager, policy analyst, etc.

- Why economic models are wrong

- The importance of simplification

- When, why, and how to use them

- Used correctly, a simple model can be a powerful tool

- Used incorrectly, the same model can lead to bad decisions

Class delivery

- Regular class meetings will in person unless circumstances force us online

- Each section will have 2 weekly in-person meetings, plus a recorded problem solving and review session

- T/TH classes during scheduled meeting times will last only (approximately) 50 minutes, supplemented by the recorded problem solving and review session

- M/W/F classes will have synchronous meetings during the first two scheduled meeting times of the week (usually M/W, unless M is a holiday) and the third class session will be the asynchronous problem solving and review class

- At least one session for each will be recorded during the week, and posted on the eClass site to allow you to catch up

Materials

eClass and my supplementary website

slides and problem sets

podcasts and other media

data

textbook

Textbook

Perloff, J. M., and J. A. Brander. Managerial Economics & Strategy. 3rd ed. NJ: Pearson, 2020.

Communication

eClass announcements

Email

Twitter

Class discussion and lecture materials

Assignments

| Task | Type | Weight |

|---|---|---|

| Flipgrid videos (4+) | online, one per month | 20% |

| Quizzes (2) | In class | 20% |

| Midterm | In class | 20% |

| Final | As scheduled | 40% |

Tips for Success

Attend class.

Take notes.

Read the readings and do the problems.

Work together.

Ask questions, participate, and attend tutorials and virtual office hours.

Don't struggle in silence, you are not alone!

Roadmap for the Semester

- Topic 1: Introduction to the class, topics and goals as well as a summary of deliverables.

- Topic 2: Supply and demand (Ch. 2 and 3)

- Quiz 1: Week of Sept 27th, details TBA

- Topic 3: The Consumer (Parts of Ch. 3 and 4)

- Topic 4: The Firm (Ch. 5, 6, 7)

- Midterm: Week of October 27th, details TBA

- Topic 5: The Market (Ch. 8, 9, 10)

- Quiz 2: Week of November 24, details TBA

- Topic 6: Competition, Strategic Behaviour, Game Theory (Ch. 11, 12, 13)

- Topic 7: When Markets Fail (Ch. 15, 16)

- Final exam: During exam period, details TBA.

Micro-economics

individual and firm decision-making

prices

labour market decisions

strategic behaviour and game theory

sports (?!?!)

marriage (?!?!)

criminal behaviour (?!?!)

pollution (?!?!)

Micro- vs. Macro-economics

- Macroeconomics studies the economy: the interactions of economic agents (people, firms, governments) over time

- Macro uses aggregates (GDP, unemployment, & inflation) and studies the behaviour of these measures in response to shocks

- Microeconomics is the study of constrained choices and consequences by individual economic agents

- Macroeconomics is what happens when you put all the micro together

What about Managerial Economics?

- Managerial economics is effectively applied microeconomics with a focus on management

- More emphasis on the theory of the firm, profit maximization, competition, and strategy

- You'll see (I hope) elements of your business plans, case studies, and other business strategy translated into a different language

What does an economist mean when they say...

- Terms you "know" from ordinary life mean very different things to economists:

Cost, efficiency, welfare, marginal, profit, public good, discrimination, elasticity, games

Using these words' "ordinary" meanings will lead to wrong economic conclusions!

You will need to "relearn" the economic meanings of these words

Is this a public good?

Economics has its own vocabulary

- You'll need to master a new vocabulary:

externality, marginal rate of transformation, marginal cost, consumer surplus, allocative efficiency

- While I'll try to avoid jargon, I'll be pedantic about certain terms with you because they are important for understanding and to convey consistent meanings

Unfortunately, an economics translator doesn't exist on Google

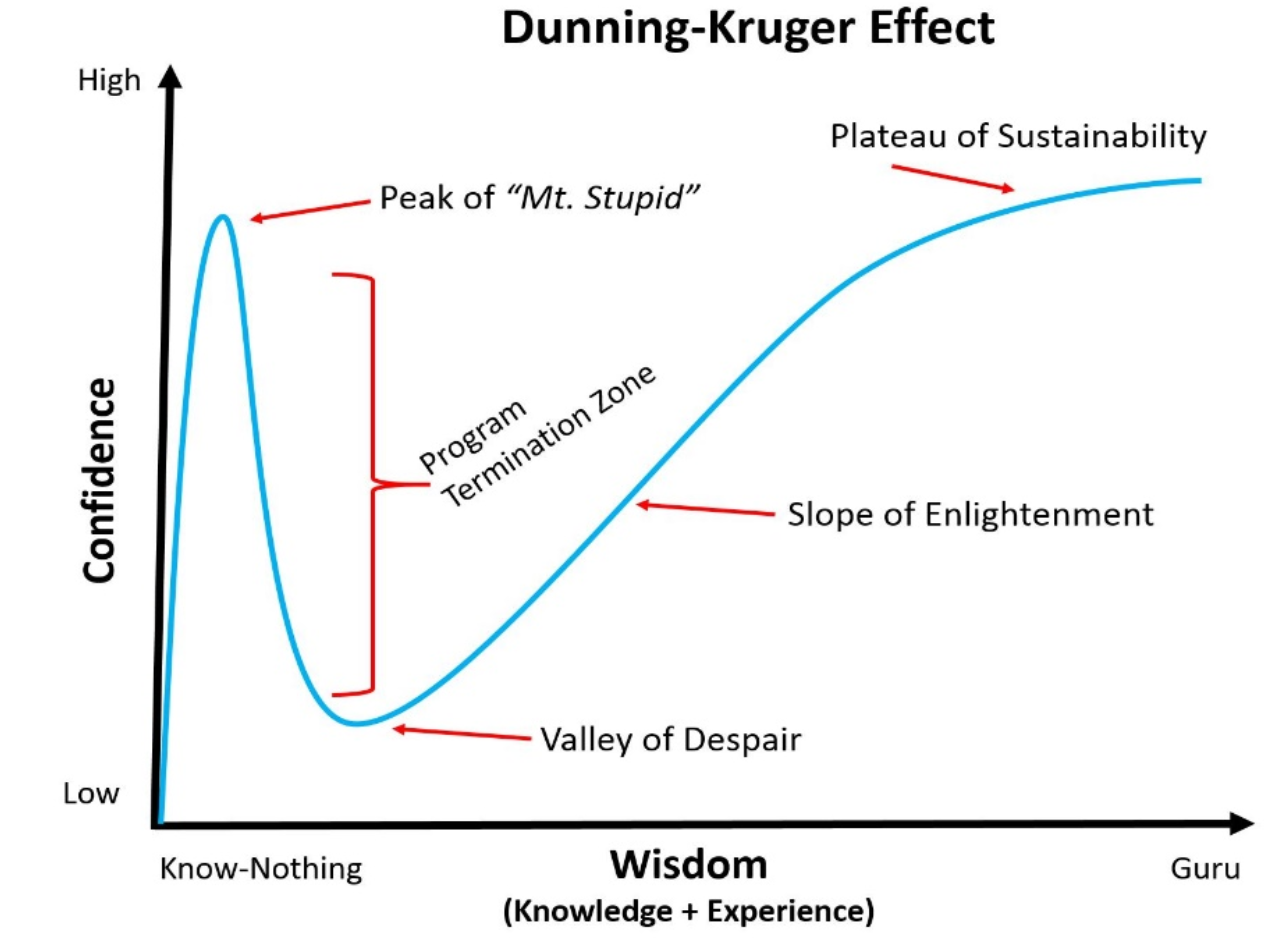

You Can Learn To Think Like an Economist

People often think they are already an economist and can speak this foreign language

Be humble, and open to new ideas

Economics is often common sense, but it takes time to grasp and apply the tools

Don't give up too soon

Economics isn't just business or dollars

Economics is a way of thinking

Dollars provide a unit of measure

Economics as a Way of Thinking

- Economics is a way of thinking based on a few core ideas:

Economics as a Way of Thinking

- Economics is a way of thinking based on a few core ideas:

- People respond to incentives

- Money, punishment, taxes and subsidies, risk of injury, reputation, profits, sex, effort, morals

Economics as a Way of Thinking

- Economics is a way of thinking based on a few core ideas:

- People respond to incentives

- Money, punishment, taxes and subsidies, risk of injury, reputation, profits, sex, effort, morals

- Environments adjust until they are in equilibrium

- People make adjustments until their choices are optimal given others’ actions

Incentives Example: Dogs on the subway

The NYC Subway bans dogs unless they can be "enclosed in a container". Source: Ryan Safner

Incentives Example: England's window tax

The British government, in 1696, was looking for a way to impose a wealth-based property tax. Solution: They imposed a tax payable based on the number of windows in your dwelling, on the premise that larger houses had more windows.

Incentives Example: England's window tax

The British government, in 1696, was looking for a way to impose a wealth-based property tax. Solution: They imposed a tax payable based on the number of windows in your dwelling, on the premise that larger houses had more windows.

Economics as a Way of Thinking

- Economics is a way of thinking based on a few core ideas:

- Economic agents have goals

- Personal satisfaction

- Profit

- Constraints impair agents' goal seeking

- Budget constraints

- Production technology

- Resource constraints

- Agents optimize subject to constraints

- Joint optimization leads to equilibrium

Equilibrium Example I

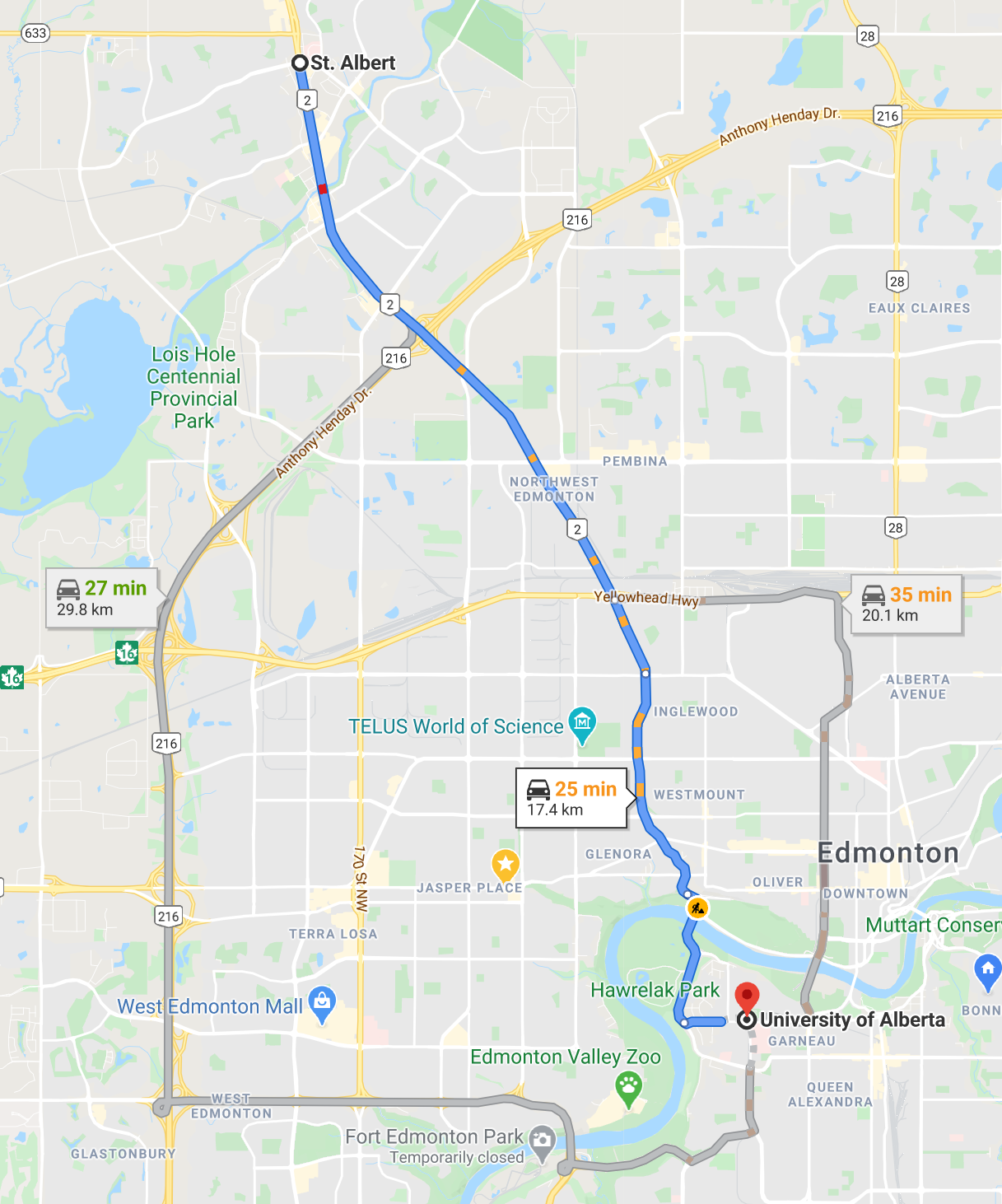

- Consider the two routes from St. Albert to the U of A

- Simplified example: 1000 cars commute

- Messier Trail / Groat Road travel time: 25 min + 1 min/ 100 extra cars

- Anthony Henday: 30 minutes (always)

Equilibrium Example I

- Consider the two routes from St. Albert to the U of A

- Simplified example: 1000 cars commute

- Messier Trail / Groat Road travel time: 25 min + 1 min/ 100 extra cars

- Anthony Henday: 30 minutes (always)

- Assume people optimize: choose road to minimize travel time

Equilibrium Example II

- Consider the two routes from St. Albert to the U of A

- Simplified example: 1000 cars commute

- Messier Trail / Groat Road travel time: 25 min + 1 min/ 100 extra cars

- Anthony Henday: 30 minutes (always)

- Assume people optimize: choose road to minimize travel time

- Scenario I: Fewer than 500 cars choose Groat Road

- What will people do?

Equilibrium Example III

- Consider the two routes from St. Albert to the U of A

- Simplified example: 1000 cars commute

- Messier Trail / Groat Road travel time: 25 min + 1 min/ 100 extra cars

- Anthony Henday: 30 minutes (always)

- Assume people optimize: choose road to minimize travel time

- Scenario I: More than 500 cars choose Groat Road

- What will people do?

Equilibrium Example IV

- Consider the two routes from St. Albert to the U of A

- Simplified example: 1000 cars commute

- Messier Trail / Groat Road travel time: 25 min + 1 min/ 100 extra cars

- Anthony Henday: 30 minutes (always)

- Assume people optimize: choose road to minimize travel time

- In Equilibrium: How many cars are on each road?

Equilibrium Example IV

- Consider the two routes from St. Albert to the U of A

- Simplified example: 1000 cars commute

- Messier Trail / Groat Road travel time: 25 min + 1 min/ 100 extra cars

- Anthony Henday: 30 minutes (always)

- Assume people optimize: choose road to minimize travel time

- What happens in equilibrium as Groat bridge is expanded, reducing commute time to 22 min + 1 min/ 100 extra cars?

Wolfers and Stevenson's Basic Principles

Wolfers and Stevenson's Basic Principles

Principle # 1: The cost-benefit principle

- What are the benefits and costs of each decision?

- Why do we measure in dollars?

- "Economists love dollars as much as architects love inches"

- Are you getting a good deal?

Wolfers and Stevenson's Basic Principles

Principle # 2: The opportunity cost principle

- Or what?

- should I take this class or that one?

- should I major in BUEC or MKTG

- should I take this job or this internship?

- What's my next-best alternative?

Wolfers and Stevenson's Basic Principles

Principle # 3: The marginal principle

- Should we buy/sell one more?

- Should we hire one more staff?

- Should I add another class to my schedule?

- Should I drop a class?

More vocabulary

- Comparative statics: examining changes in equilibria cased by an external change (in incentives, constraints, etc.)

- Most of what we do in this class will fall into this category

- Comparative dynamic analysis is possible but much more challenging: math is harder when it moves!

More vocabulary

If economic agents can learn and change their behavior, they will always switch to a higher-valued option

If there are no alternatives that are better, people are at an optimum

If everyone is at an optimum, the system is in equilibrium

Wolfers and Stevenson's Basic Principles

Principle # 4: The interdependence principle

- All else equal...but is it?

- What happens to my best decision when other factors change?

- Does my value depend on what others do? Network externalities?

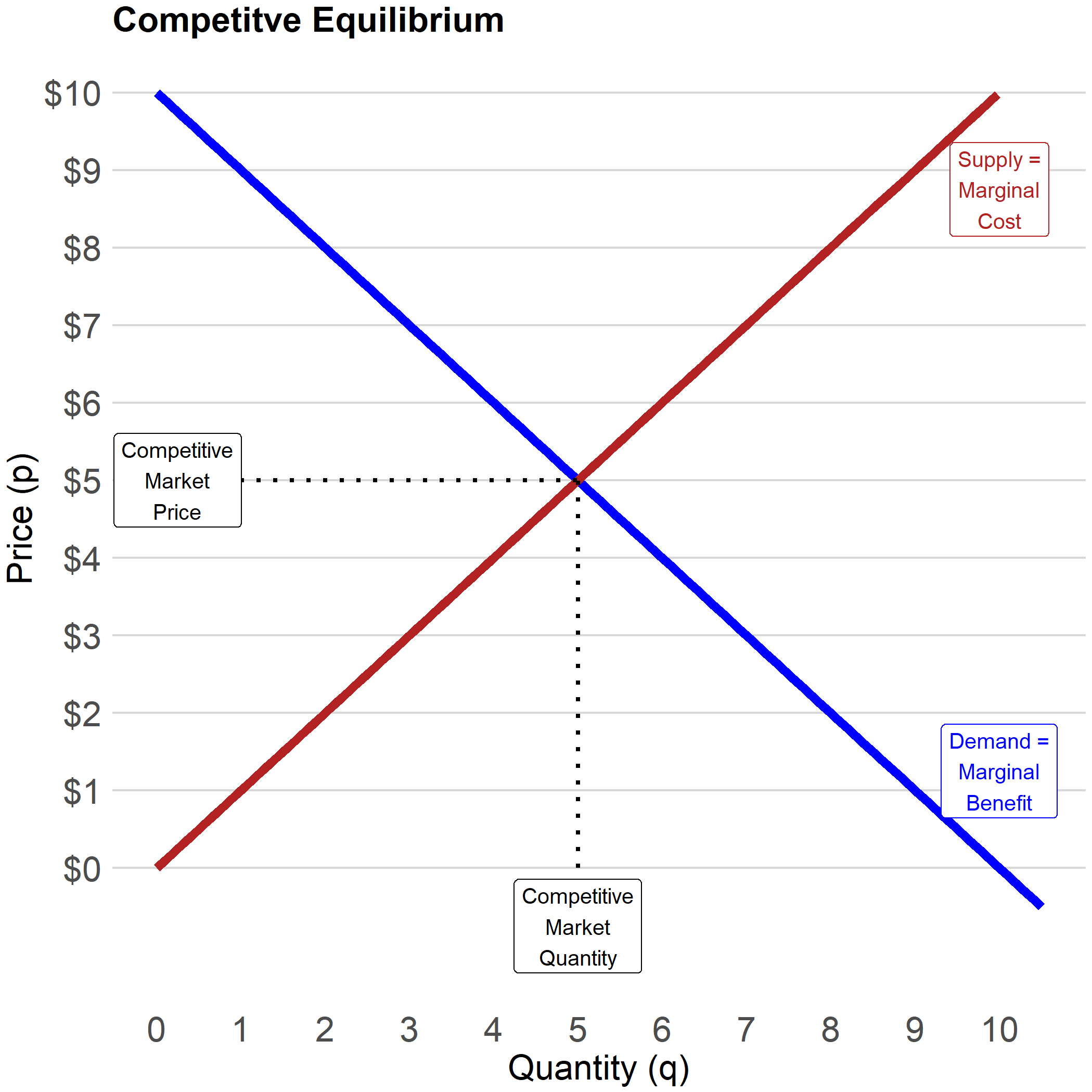

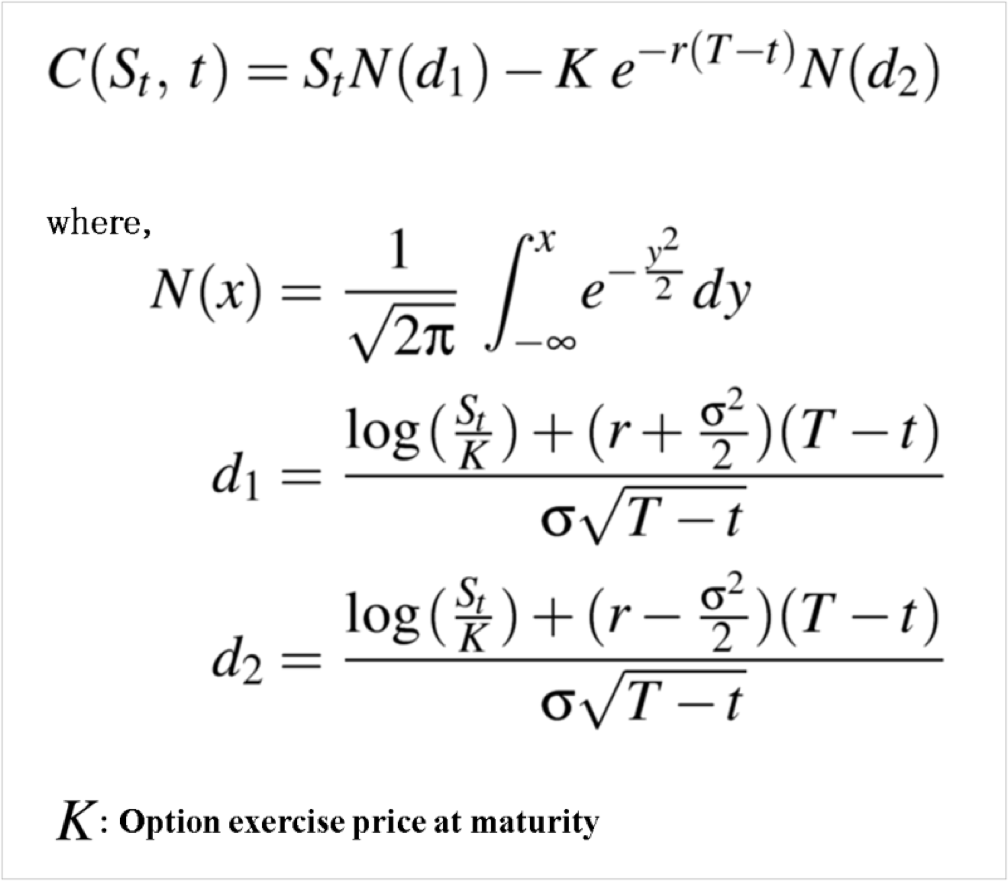

Why We Model I

Economists often "speak" in models that explain and predict human behavior

The language of models is mathematics

Mathematical inference is expressed through equations and graphs

This is what scares students most about economics. Don't let it scare you.

Why We Model II

Economists use conceptual models: fictional constructions to logically examine consequences

Economics is broader than just mathematical models:

- Economists run experiments

- Economists analyze data

- Economists make predictions

Math is a tool, it's not the goal

Remember: All Models are Wrong!

Caution: Don't conflate models with reality!

Models help us understand reality.

A good economist is always aware of:

- the limits of their model

- the key underlying assumptions

- " ceteris paribus " (all else equal)

- "...and then what?" (is the system in equilibrium?)

- "...compared to what?" (counterfactual analysis)

Economics uses, but is not limited to, math

Positive and Normative Statements

- Economics alone can't tell you the right decision

- A positive statement is a statement of what is or what will happen and describes reality.

- If you increase the costs of production, consumer prices will go up.

- Positive statements can reflect uncertainty about outcomes

- A normative statement concerns what somebody believes should happen:

- “The government should tax greenhouse gas emissions.”

- Normative statements cannot be tested because they imply value judgments which cannot be refuted by evidence.

- Normative statements can inform objective functions

- A decision-maker might look for a policy which does not increase inequality

- Economists can provide constrained advice: this policy accomplishes your objective and is unlikely to increase inequality